Race and Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Methods, Sources, and Assessments

Race and Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Methods, Sources, and Assessments

Race via AFROCENTRISM

Afrocentrism is a movement in the humanities to focalize – rather than view as an object, responder, or colonized subject – the African continent. While this explicitly anti-racist approach was pioneered by Drusilla Dunjee Houston in her 1926 book Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire, and was carried on by scholars such as Cheikh Anta Diop, its implications for ancient studies have become most apparent since Martin Bernal published his extremely influential and controversial multi-volume book Black Athena in the 1980s. In Classics and Ancient Studies, Afrocentrism has primarily been utilized as a lens for exploring Egypt’s relationship to Nubian and Sub-Saharan African cultures. The following sources explore methods and case studies of Afrocentrism that examine not only Egypt, but also Nubia, Ethiopia, and Pan Africanism.

Bernal, Martin. Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. Rutgers University Press, 1987.

Presented in three equally monumental volumes, the first published in 1987, Bernal’s Black Athena is perhaps the most controversial work in the modern discipline of Classics. Bernal, the grandson of one of the twentieth century’s most famous Egyptologists, was a scholar of ancient China by training. As a result of studying Semitic languages and cultures, Bernal found new interest in what he saw to be the Afroasiatic roots of Greek civilization. In essence, Bernal asserts that cultural, linguistic, and religious similarities demonstrate that Greek civilization took its lineage – as Herodotus and other ancient authors assert – from Egyptian civilization, making Classical civilization ultimately of African heritage. Although the evidence he mobilizes has been frequently contested, Black Athena is important in that it explores the various ways in which Classics as a discipline has been invested in closely guarding the purity of its European roots. Bernal’s text-- which won the American Book Award-- generated widespread debate in the field of Classics, but its reception in Black studies and other areas has been largely positive and productive (ALR, 2020).

Further reading on Black Athena and its tumultuous reception can be found in Denise McCoskey’s article in Eidolon, “Black Athena, White Power.” See also Mary Lefkowitz’s hearty rebuke of Bernal in her book, Not Out Of Africa: How "Afrocentrism" Became An Excuse To Teach Myth As History, to which Bernal responded in his 1987 work, Black Athena Writes Back.

Cheikh Anta Diop. The African Origin of Civilization: Myth Or Reality. Lawrence Hill Books, 1974.

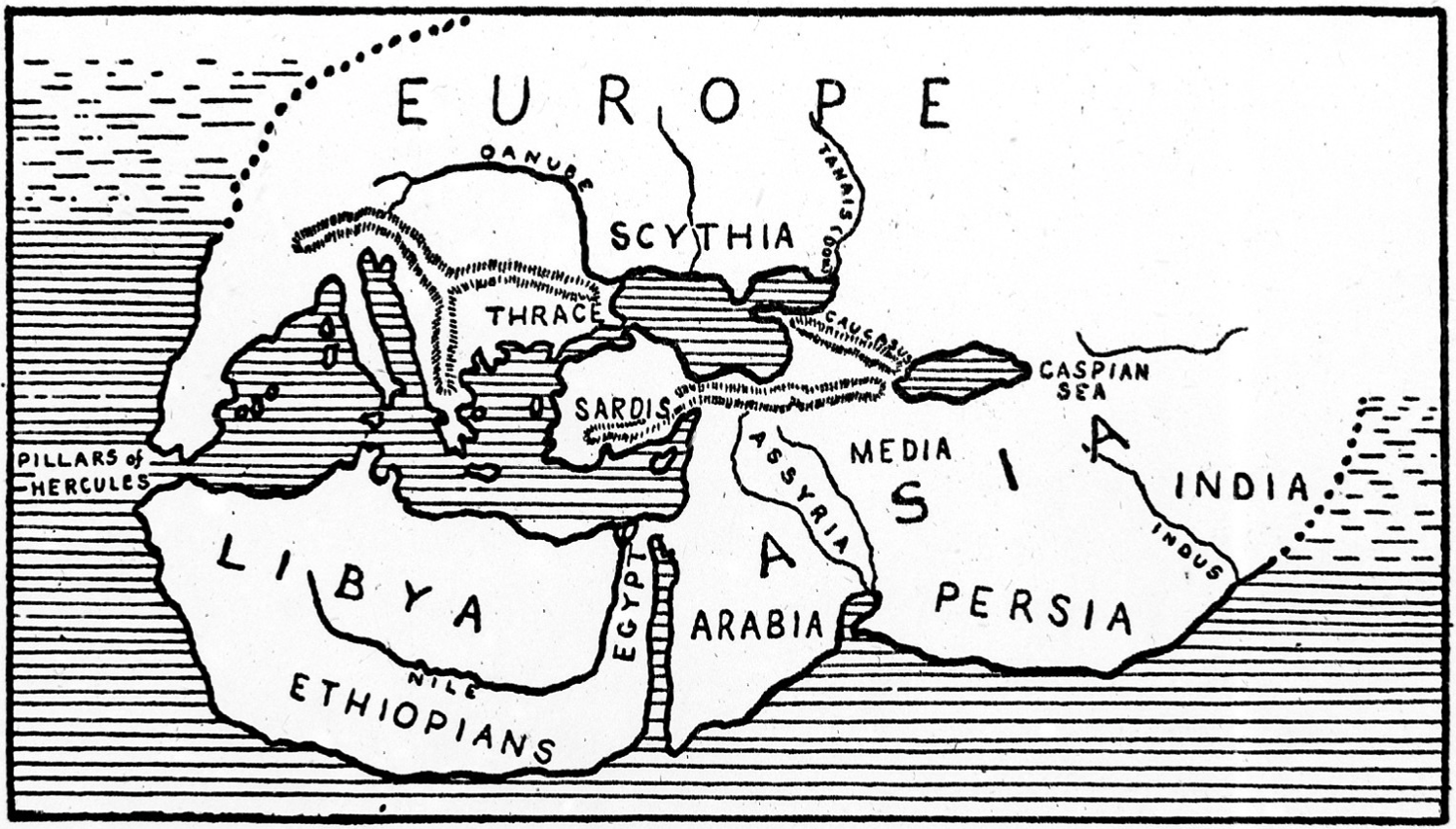

Cheikh Anta Diop, born in Francophone Senegal, wrote numerous histories that offered a cohesive account of Africa’s ancient past. His most frequent focus was on Ancient Egypt. Diop believed that racial-ethnic terminology such as “Mediterranean,” “Middle-Eastern,” and even “Caucasian” served to dissociate Egypt from its African identity and tradition. Importantly, Diop wanted the term “black,” in academic literature and common vernacular, to have as broad a meaning as the term “white,” leading him to write numerous histories of Egypt that focused on the Blackness of the population. Like Bernal, Diop is a controversial figure in the academy. However, his view that Egypt should be viewed as a thoroughly African civilization, and many of his insights and observations, are important (ALR, 2020).

Keita, Maghan, “Deconstructing the Classical Age: Africa and the Unity of the Mediterranean World." Journal of Negro History 79 (2), 1994.

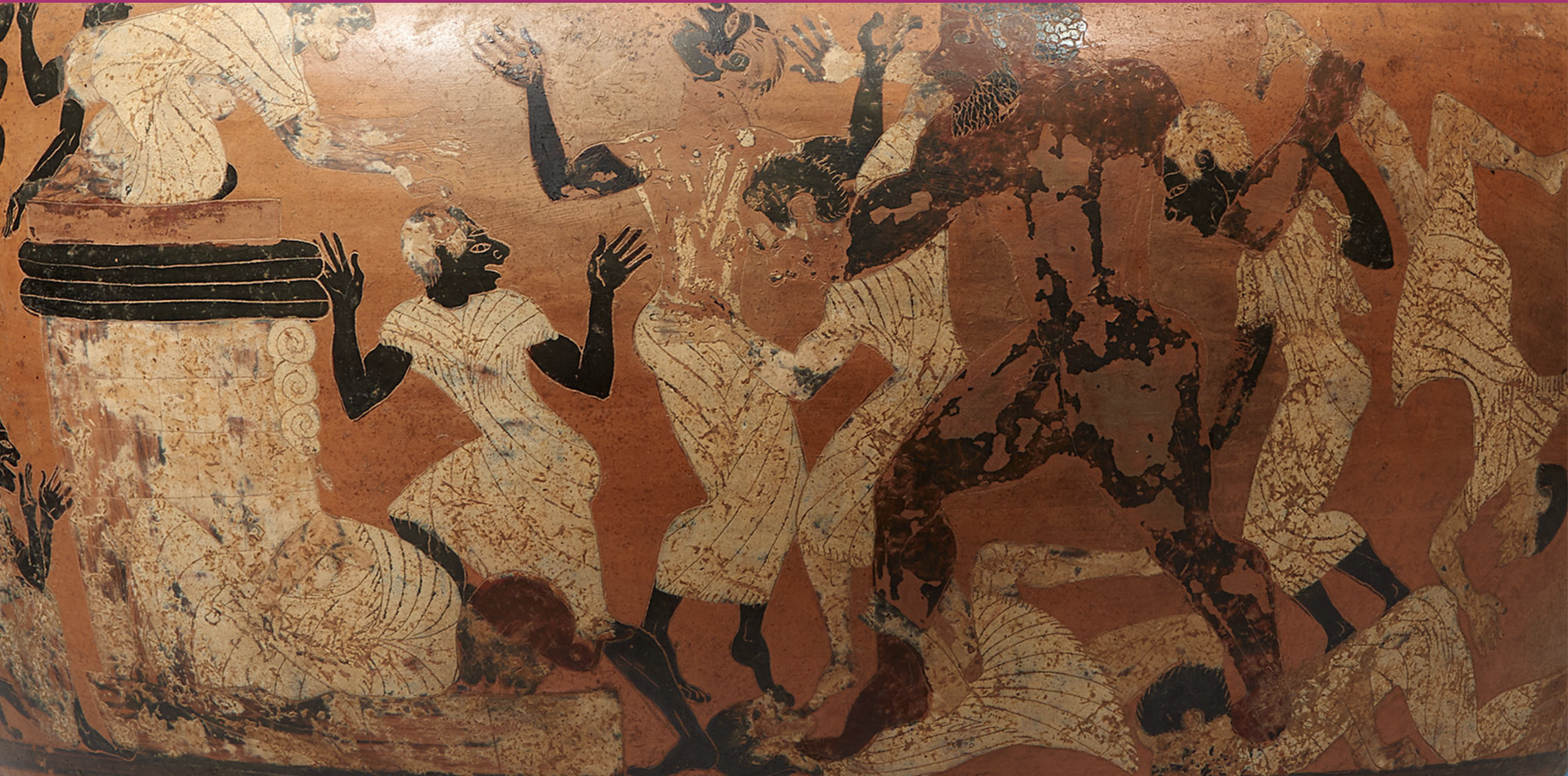

In a rebuttal to arguments that Africa was peripheral to a fundamentally European Classical culture, Maghan Keita highlights the importance of Aethiopians for Homer, North Africans for Herodotus, and Carthage for Romans. Foundational to her argument that Africa played a vital role in the self-conception of ancient Greeks and Romans are mythological lineages. The Greek hero Perseus, for example, was a descendant of Danaus, the ancient king of Libya, whose brother Aigyptos ruled Egypt. Further, a crucial element in Perseus’s heroic narrative was his rescue of the beautiful maiden Andromeda, the daughter of the king and queen of Aethiopia. According to Herodotus, the Greek strongman Hercules had been born from Egyptian parents and performed many of his feats in northern Africa. These narratives and others like them demonstrate the integral presence of Africa in the heroic self-conception of ancient Greeks. Both within historical and mythological milieus, Keita provides plentiful evidence that "the African, far from being separated from Classical civilization, was, in fact, an intrinsic and integral part of it" (TNK, 2023).

Malamud, Margaret, 'Black Minerva: Antiquity in Antebellum African American History', in Daniel Orrells, Gurminder K. Bhambra, and Tessa Roynon (eds), African Athena: New Agendas, Classical Presences, 70–89, (Oxford, 2011; online edn, Oxford Academic, 19 Jan. 2012).

In the fourth chapter of African Athena: New Agendas, Margaret Malamud explores the promotion by abolitionists of African and European heritage of a racial linkage between African Americans and pharaonic Egyptians. Through embracing an ancestral tie to one of the world’s most esteemed cultures and claiming a shared classical heritage, Black intellectuals sought to defend their assertion of racial equality. As modern descendants of a civilization that predated Greece and, indeed, civilized it, Black people not only fought against the myth of Social Darwinism but for the first time they inserted their African identities into a historical narrative. Referencing descriptions embedded in classical sources—primarily Book II of Herodotus’ Histories—these original Afrocentrists pointed to the racial similarities between modern black people and the Egyptians, Ethiopians, Carthaginians, and Colchians. By racially linking African Americans to these civilizations and then praising their military, intellectual, and cultural dominance over the classical world, they argued that black people were neither intrinsically racially inferior to white people nor unable to be “re-civilized.” White supremacist scientists, not surprisingly, stridently sought to disprove any characterization of Egyptians as black. While Malamud highlights the empowering nature of this embrace of Egyptian heritage, she ends by noting that it would not be until the Harlem Renaissance that black intellectuals took pride in the Africa of their day (TNK, 2023).

Snowden, Frank. Blacks in Antiquity. Harvard University Press, 1970.

In his far-reaching project, Frank Snowden, renowned professor of Classics at Howard University, presents a history of Blackness in the ancient world through a transdisciplinary examination of “Ethiopians.” Ethiopian, as Snowden demonstrates, became in the Greco-Roman world a catchall term for Black-skinned individuals, and particularly those from regions south of Egypt's first cataract. Obvious divisions existed among those in this racial category, and Snowden demonstrates the rich and varied nature of the surviving evidence. Using archeological, historical, and literary sources from both Greek and Roman civilizations, Snowden foregrounds and illuminates the heterogeneous experiences of Africans in contexts of culture contact. In doing so, he problematizes the notion that modern biases can be easily transposed upon the peoples of the ancient world. This is an excellent text for those seeking visual and material sources regarding race in antiquity (ALR, 2020).

Snowden, Frank. Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks. Harvard University Press, 1983.

A decade after Blacks in Antiquity, Snowden wrote Before Color Prejudice. Snowden’s essential supposition in the text-- that not only was there no color prejudice against Black Africans in antiquity but that the group was by and large highly favored and respected-- is a complicated view. Snowden argues that while "Ethiopians" (mostly Nubians and sub-Saharan Africans) encountered in the classical world as slaves suffered from the stigma common to all slaves, rich Ethiopians were respected and their poorer counterparts were not discriminated against on the basis of their skin color. Thus, Snowden offers an image of race in the ancient world that rewrites the assumptions of post-colonial logics. Race and racial projects are largely about power; thus, the fact that-- unlike Egypt-- "Ethiopia" remained unconquered meant, in Snowden's view, that its people could be known for other traits such as piety and righteousness. It’s important to note that Before Color Prejudice was met with skepticism by some Black scholars in other departments, famously Orlando Patterson, whose 1982 text Slavery as Social Death served as antithesis to Snowden’s. To some extent such differences in opinion rest on whether one privileges literary satire, artistic caricature, and evidence for Black slaves or whether one focalizes instead the plentiful evidence for flattering depictions of free Ethiopians in art and text (ALR, 2020).

Race via ARCHAEOLOGY & MATERIAL CULTURE

When it comes to approaching race in the ancient world, the largest barrier is evidence, the qualifications for which are ever-shifting and often impossible to meet. Insofar as ethnic and racial identities often overlap, the work of archaeologists in exploring the material artifacts of antiquity can provide an important window into past constructions of identity. This is particularly true with reference to non-elites and to women. Thus, archaeology often serves as an irreplaceable counterbalance to the biases inherent in ancient written evidence and artistic production. The following sources not only present findings from excavations but include theoretical frames. Some, however, focus less on evidence than they do on ethics and argue for re-envisioning the discipline.

Angelis, Franco de. “New Data and Old Narratives: Migrants and the Conjoining of Cultures and Economies of Pre-Roman Western Mediterranean,” in Homo Migrans. Modeling Mobility and Migration in Human History, ed. M.J. Daniels SUNY. 2022.

In situations of culture contact, encounters between distinct ethnic or “racial” groups have often historically been framed as having occurred between “backwards” indigenous peoples and more “advanced” immigrants. Franco de Angelis set out to investigate the veracity of such an entrenched colonialist narrative with respect to the pre-Roman western Mediterranean from the ninth to the third centuries B.C.E. He juxtaposes this historical paradigm, which views the region as primitive until the influx of the supposedly superior Greeks and Phoenicians, with an emergent postcolonial narrative that foregrounds local agency and achievement. De Angelis points out that these polarized frameworks have largely resulted from contrasting the civilizing narratives found in classical texts with archaeological evidence. His own intervention is to test new metallurgical and economic data against a model designed to assess backwardness. In the end, de Angelis concludes that the two paradigms are both problematic, as is a stark dichotomy between “local” and “foreign.” Within a couple of generations, he points out, such foreigners had themselves become local. (SC, 2024)

Bonnet, Corrine. “On Gods and Earth: The Tophet and the Construction of a New identity in Punic Carthage,” In Cultural Identity in the Ancient Mediterranean, ed. Erich Gruen, Getty Publications, 373–387, 2011.

Corrine Bonnet looks at archaeological evidence of ritual tophet structures in Punic Carthage, which are usually tied to an etic idea of Punic traditions of human sacrifice. As little written material from the colony survives, it is impossible to construct a purely emic understanding of the significance of the tophet and practices of human sacrifice based on written records. The chapter examines the unique position of Carthage as a colonial settlement that interacted with the indigenous population of North Africa and as a diaspora community with close ties to Phoenician culture and identity. It places its material culture in dialogue with the ideas of Punic-Carthaginian ethnicity as viewed from an etic Greek and/or Roman perspective. Punic-Carthaginian ethnicity and identity could be expressed, Bonnet argues, by the presence and ritual use of tophet structures in and outside of Punic Carthage. (LC, 2021)

Buzon, Michele. “Nubian identity in the Bronze Age: Patterns of Cultural and Biological Variation.” Bioarchaeology of the Near East 5: 19–40, 2011

Michele Buzon wanted to understand the differences between two Nubian groups—the C-group and Kermans—using both bioarchaeology and material culture. In terms of bioarchaeology, Buzon took twelve different cranial measurements from 282 C-group remains and 291 Kerma remains. These results were analyzed using T-tests alongside a method called PCA which had mixed results. Although there was no significant difference in the shape of the cranium between the groups, there were differences in cranium size. Buzon suggests that the C-group’s crania may have been smaller due to environmental stressors, as the C-group inhabited a much more arid climate than the Kermans. Buzon notes that despite the relatively few observable biological variations, the pottery and burial practices of the groups were quite divergent. C-group pottery includes red-burnished ceramic wares that had black incisions as well as blackened mouths or tops. Kerman pottery did not have those distinctive designs. In terms of mortuary tradition, there are similarities in the position of the bodies; that said, they are overshadowed by differences. These include the fact that Kerman burials included more of a superstructure and ornamentation, and military items constituted part of the burial assemblage. By contrast, C-group burials were simple and relatively egalitarian, making it difficult to tell the graves of royals from the rest. Because of these important cultural differences in this era, Buzon concludes that the two groups made an active effort to emphasize the ethnic and societal features that were important to them. (KM, 2023)

Carr, Gillian. “Creolisation, Pidginisation and the Interpretation of Unique Artefacts in Early Roman Britain.” Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal 0: 113–125, 2002.

As imperial Rome spread its dominion, it is often considered to have been completing the civilizing process of ‘Romanization.’ However, as Carr argues in this text, this is an outdated model. Romanization is really just a specified form of acculturation, which is a term that has been used historically as a unidirectional process of a dominant society implanting its cultural norms onto a subjugated society. Modern scholarship would argue that we should instead be considering multidirectional cultural exchange when we look at boundaries and interactions between ancient societies. Here, Carr employs the linguistic concepts of creolization and pidginization to analyze the material culture of early Roman Britain. So too, she asks if we can find people creating ‘pidgin’ artifacts in the wake of foreign infiltration and interactions. Carr argues that we cannot understand the Romans and the Britains to be two opposing, monolithic groups, because the archaeological record includes items that blend both societies. Carr demonstrates in particular how creolization is important because it allows “the non-elite native voice to be heard within the complex mix of hybrid Roman and non-Roman identities and counter-cultures which made up Roman Britain.” Carr’s approach in this work – using analytical tools usually applied exclusively to language formation in colonial settings – is an innovative alternative to outdated theories regarding colonizer-colonized relationships. (HC, 2021)

Finkelstein, I. " Ethnicity and Origin of the Iron I Settlers in the Highlands of Canaan: Can the Real Israel Stand Up?" The Biblical Archaeologist 59 (4): 198–212, 1996.

Israel Finkelstein argues against types of material culture (e.g., the four room house, collared rim storage jars, etc.) being interpreted as cultural signatures of early Israelites. He maintains that a migration from the lowlands to the highlands in the Iron Age I period (1200-1000 BCE) should not be considered the origin point of Israelite identity. Finkelstein explains that pottery variations are regional and stem from economic, environmental, and social factors. They are not reliable indicators of ethnicity. He further suggests that the migration that took place in Iron Age I should be considered the third wave in a long-standing settlement pattern in the highlands. Before the Iron Age, the highlands had experienced two waves of settlement as a response to climatic and social factors. In each prior case, settlers had shortly thereafter returned to a pastoral existence. The third wave of settlers, however, resulted, much later, in the early-Israelite kingdom attested in Iron II. While a taboo on pork among highlanders, evident in the Iron I period, may perhaps suggest an emergent communal sense of self, Finkelstein maintains that a coherent “Israelite” past—with its canonical narration of migrations and early Iron Age I rulers—was largely fabricated by Judean priests and rulers in the late Iron Age II (c. 9th -8th centuries BCE) to enhance social and religious cohesion, bolster the state against threats from neighboring polities, and provide retroactive support for their aspiration to control land from Galilee to the Negev. (AF, 2024)

Fitzjohn, M. “Constructing Identity in Iron Age Sicily.” In Communicating Identity in Italic Iron Age Communities, ed. Margarita Gleba and Helle W. Horsnaes, Oxbow Books, 155–166, 2011.

In this article, Matthew Fitzjohn explores how domestic spaces manifested aspects of ethnicity and identity in the Iron Age Sicilian site of Lentini. Several different ethnic groups can be identified at the site including Sikel, Sikan, Elymian, Phoenician, and Greek. Fitzjohn highlights the ways in which the combination of these identities is reflected in the architecture of this site. He first delves into how methods of construction are as important as the forms of the buildings themselves. Social relationships were required for the mobilization and creation of these structures, thus demonstrating the presence of community-building efforts at Lentini. Indeed, Fitzjohn emphasizes that for those who do not have previous experience in construction, the process of learning is an important part of becoming a “fully participating member of society.” Fitzjohn also describes how the forms of architecture that emerged at Lentini during this period were not characteristic of one distinct ethnic group but rather reflected the intermingling and combination of different groups. For instance, the rock-cut houses of Lentini contained features that come from both Greek architectural tradition as well as indigenous architectural traditions. The combination of different architectural traditions into the same domestic structures highlights the creation of “a new form of cultural space.” In conclusion, Fitzjohn urges readers to examine the architecture of Lentini differently, moving past strict demarcations of ethnic groups and rather examining the data through more complex interpretations of how the inhabitants of Lentini characterized their identities and cultural spaces. (OT 2023)

Frankel, David, and Jennifer M. Webb. “Three Faces of Identity: Ethnicity, Community, and Status in the Cypriot Bronze Age.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 11: 1–12, 1998.

David Frankel and Jennifer Webb establish three aspects of identity (ethnicity, community, and status) and discuss how these variables manifested in the Early, Middle, and Late Bronze Ages in Cyprus, as supported by archaeological evidence. The authors discuss ethnicity in the Early Bronze Age through a method that separates ethnic groups by their habitus. Habitus, a term coined by Pierre Bourdieu, is “an inclusive conceptualization of the entire social and material constitution of social groups, worked out in action.” By associating habitus with ethnicity, Frankel and Webb demonstrate the division in Early Bronze Age Cyprus between two ethnic groups: an indigenous Chalcolithic community and a newly arrived Philia people. This division is seen in a variety of archaeological evidence, from distinct building styles to cooking methods. In their investigation of pottery styles in the Middle Bronze Age, Frankel and Webb emphasize the importance of thinking about community. At this time, Cypriots possessed a single habitus and thus were ethnically homogeneous. Regional variations in ceramic style, however, aided local communities in asserting their own identities. Finally, the authors examine the use of seals as a marker of socio-economic status during the Late Bronze Age. Three styles of Cypriot cylinder seals each signified the different social statuses of their owners: the “Elaborate Style” denoted high status, the “Derivative Style” a middling status, and the “Common Style” a (relatively) low status. In addition to being differentiated by their aesthetics, the three styles were distinguished by the status of the entities depicted upon them. The Elaborate Style, for instance, often showcased the presence of deities. By contrast, the Derivative Style depicted more “semi-divine” entities (like the griffin in the image below), while only mortals appeared in the Common Style. (AG, 2023)

Fuller, Dorian. “Early Kushite Agriculture: Archaeobotanical Evidence from Kawa,” Sudan & Nubia 8: 70–74, 2004.

This work discusses plant remains from 8th-5th century BCE Kawa, a major urban center of the Napatan state in Nubia. Evidence of dates and grape plants may indicate the possibility of a plantation economy, which would have been made possible by the new irrigation systems introduced as a result of New Kingdom Egyptian colonialism. Fuller argues that the intensive agricultural work necessary to maintain such crops would have impacted conceptions of ethnicity in the region, as large groups of people would by necessity have been brought together, thus likely resulting in transculturation. So too, the shift to new crops may have caused a change in culinary habits—thereby affecting the foodways that constitute a key signifier of ethnic identity for many groups. (SJ-F, 2021)

Gur-Arieh, Shira, Elisabetta Boaretto, Aren Maeir and Ruth Shahack-Gross,) “Formation Processes in Philistine hearths from Tell es-Safi/Gath (Israel): An Experimental Approach.” Journal of Field Archaeology 37 (2): 121-131, 2012.

The pebble hearth has been identified by archaeologists as an ethnic marker for the presence of Aegean migrants in the Early Iron Age southern Levant. In this article, the authors reconstructed excavated hearths to see how different modes of use would impact them and whether interpretations of soot patterns on pottery and hearths in Philistia and the Aegean reflected use-patterns. Their Philistine hearths were made using local materials at Tell es-Safi/Gath. The function of the pebbles was unclear, and the sudden explosion of hot pebbles in the hearth – alongside the rapid rate of heat loss from the pebbles to the air, compared with clay soil, may have meant that Philistine hearths were primarily used for low temperature cooking over long spans of time. They suggest that the pebbles served to spread heat further from an active fire at the center of the hearth so that food could be placed on the hot pebbles to cook, roast, or bake. Soot patterns on the cooking jugs, they concluded, came not from proximity to the fire but rather from exposure to the wind. (CH, 2023)

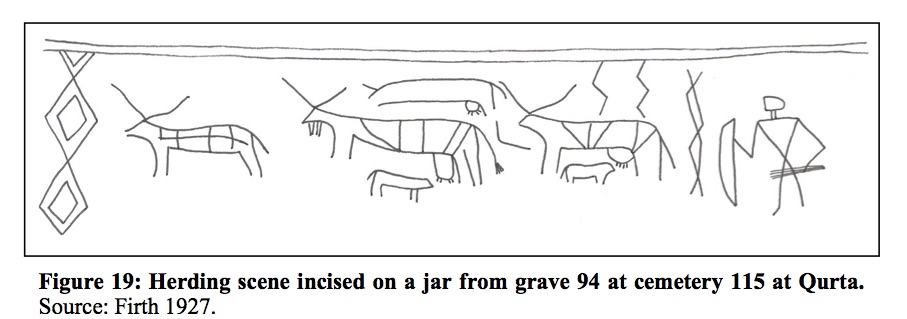

Haafsas, Henriette. Cattle Pastoralists in a Multicultural Setting: The C-Group People in Lower Nubia (2500 to 1500 BCE). Birzeit University, 2006.

This book investigates the ethnic identity of the C-group people of Lower Nubia and how their cattle pastoralist lifestyle impacted their culture. While much is still not known about the C-Group, as they did not have a literary tradition, much can be extrapolated from their art, funerary practices, and the impression they left on their literate Egyptian neighbors. This article provides an overview of the C-group’s cultural trajectory from its presumed ethnogenesis in the late Old Kingdom until its seeming disappearance in the early New Kingdom. It also draws on ethnographic studies of cattle pastoralist societies to argue women were very likely responsible for milking and therefore also for manufacturing pottery. If so, women would have had a significant role in manufacturing many of the material signatures that archaeologists utilize to identify the culture ethnically. (SJ-F, 2021)

Jansari, Sushma. “South Asia,” In The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek World, ed. R. Mairs. Routledge, 38-55. 2020.

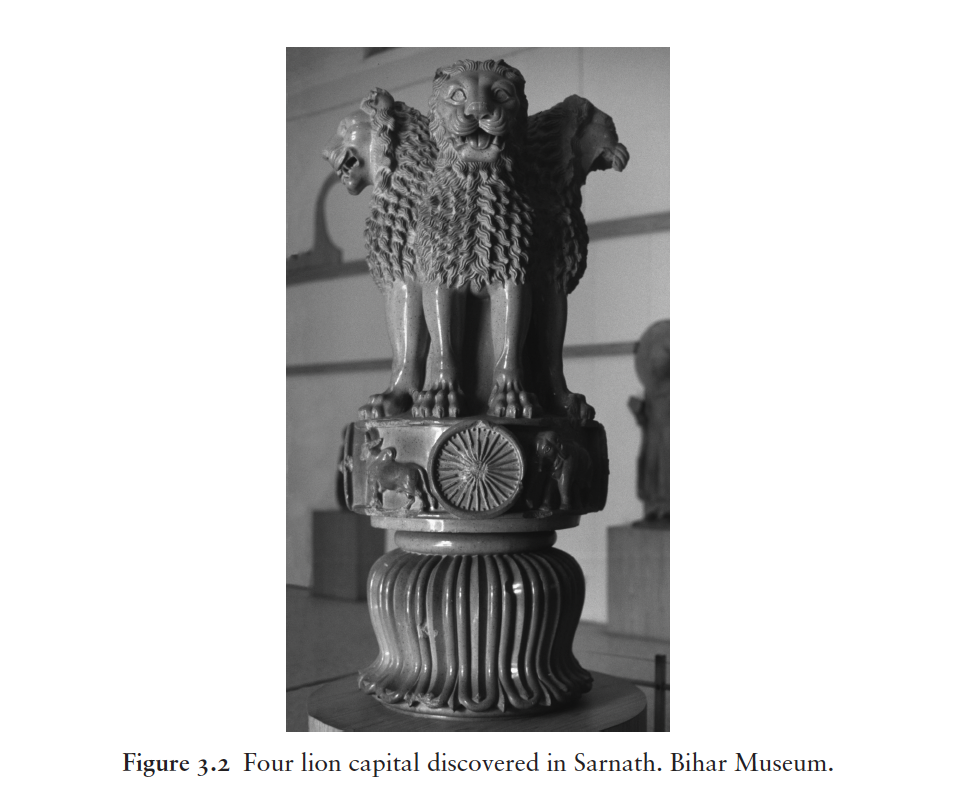

Sushma Jansari studies the Indo-Greek world using Aśokan pillars as a focal point. The sixteen tall sandstone columns with distinctive tops, found throughout the Ganges valley and Nepalese Terai, are generally thought to date back to Emperor Aśoka's rule from 268 to 232 BCE. Inscriptions on some of the pillars mention Aśoka's pilgrimage to Buddhist sites, a narrative supported by ancient Chinese pilgrims Faxian and Xuanzang. Yet, some scholars doubt that the monarch could have commissioned all of them, given their wide geographical distribution, the variety in their quality, and the fact that a stylistically identical pillar at Deur Kothar bore a dedicatory inscription from a Buddhist monk. Thus, it is possible that other influential individuals may have also commissioned such pillars. These monuments were set up at important religious sites along routes used for pilgrimage. The discovery of rare materials like lapis lazuli and carnelian at these sites, and the fact that pilgrimage routes were also employed by traveling merchants on their journeys, points to the early importance of trade and trade routes in spreading both Buddhism and an influential iconography that signalled ethnic identity and power. The use of the pillars to mark important religious sites, along with the stupas that Ashoka built near some of them as places for devotional practice, were fundamental in spreading Buddhist teachings. Their importance continued over the centuries, with later leaders moving them or adding their own inscriptions. That the four-lion top of the Sarnath pillar—erected at the site at which the Buddha preached his first sermon—was made India's emblem in 1950 demonstrates the lasting resonance, even to a secular democratic state, of Aśoka's efforts to forge a powerful state centered on Buddhist teachings. (DN, 2024)

Mac Sweeney, Naoíse. “Beyond Ethnicity: The Overlooked Diversity of Group Identities.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 22 (1): 101-126, 2009.

Western Anatolia in the Late Bronze Age has been traditionally viewed as an intermediate zone between the western Greeks and the eastern Hittites. Given this geographical context, scholars have discussed the societies living within this “in-between” area in terms of ethno-cultural identities that blend elements from Greek and Near Eastern constructions of ethnicity. Yet the diverse range of societies within western Anatolia could have been unified by collective identities that were not determined by Greek and/or Hittite ethnic identity—or by ethnicity at all. Challenging the predominant focus of current studies on ethnicity when discussing group identity, Mac Sweeney proposes that scholars should not assume that group identities are always based on ethnicity. Instead, one should investigate any commonalities that may underlie the formation of specific group identities, including religious, linguistic, ethnic, social, or political factors. To argue this point, she examines the “fluid and changeable” group identities at the western Anatolian site of Beycesultan. Mac Sweeney reviews archaeological findings in Beycesultan for deliberate practices of group affiliation, ultimately concluding that conscious articulations of group identity were not constant but instead manifested by specific social and historical circumstances. For example, communal dining practices at Beycesultan in the Late Bronze Age utilized only local styles, possibly as a response to the unwelcome encroachment of the Hittites. However, any collective group identity expressed through material culture had vanished by the Early Iron Age, likely because foreign styles no longer indicated unwelcome political affiliations. (RT, 2023)

Roymans, Nico. “Conquest, Mass Violence and Ethnic Stereotyping: Investigating Caesar’s Actions in the Germanic Frontier Zone.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 32: 439–58, 2019.

Paying special attention to the terminologies and ideologies attendant to “mass violence” and its examination in antiquity, Roymans’ article considers moments of contact between the indigenous population of Gaul and the technological developments in warfare heralded in by Caesar’s armies. Alongside material from Caesar’s own Commentarii, Roymans reads the archeological remnants of the Germanic frontier in order to excavate the “demographic impact” of these moments of conquest. While building to a larger exploration of stereotyping of the Gauls and how this played a role in the violence committed against them, Royman’s piece is heavily invested in the locality of Germanic frontier and considers closely how the specificity of place enables certain forms of extreme violence. Royman’s archeology, which leans upon post-colonial theory, productively and originally presumes that material culture may help surface extreme forms of warfare and trauma more than their literary counterparts, and in this helps underscore a new way of reading the ethnographic imprint of warfare and the huge impact of racially motivated violence in antiquity. (ALR, 2022)

Rothman, Mitchell. “Early Bronze Age Migrants and Ethnicity in the Middle Eastern Mountain Zone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (30), 2015.

Identifying meaningfully coherent ethnic groups in deep prehistory is a difficult task, yet Mitchell Rothman believes it is important to attempt, as ethnicity as a concept can wield great explanatory power. Rothman embraces what he calls the modern anthropological definition of ethnicity, which specifies that ethnicity only occurs in heterogenous societies in which difference is recognized and ascribed meaning. He likewise emphasizes that ethnicity is never static. Rothman analyses the Kura-Araxes cultural tradition of 3500-2450 BCE, which arose in the Caucasus Mountains and spread to other mountainous regions due, he suggests, to the desire of those who emigrated to take advantage of new economic activities centered on viniculture, metallurgy, and wool production. When people who bore this culture—with its distinctive ceramic, architectural, and ritual traditions—settled among those who spoke different languages and practiced different traditions they became “effectively ethnic groups” who eventually assimilated into the local cultures. Rothman ends by stating that this process, though it happened some five millennia ago, should not be consigned to the past. In the United States, for instance, many “people of distinct and strong ethnic identities” have migrated for economic opportunity and underwent “a similar process of assimilation” in which they lost some elements of their ethnic identity and incorporated others into a new and heterogeneous shared culture. (AR, 2024)

Shepherd, Gillian. “Archaeology and Ethnicity. Untangling Identities in Western Greece.” Dialogues d'histoire ancienne 10: 115–143, 2014.

Gillian Shepherd focuses on ethnic identity in ancient Sicily during a time when the island was home to native Sicilian populations, as well as Greek and Phoenician colonies/city-states. Thucydides, as well as other literary sources, offer insights into the etic perspectives of identity in ancient Sicily. Thucydides details the mother cities of Greek colonies in Sicily, the presence of Phoenicians, and the three main Sicilian native groups as Sicans, Elymians, and Sikels. Despite this clear delineation of ethnicities set forth in the ancient textual record, Shepherd argues that the material evidence of Sicily does not reflect these same clear-cut boundaries. The material culture of the native, the Phoenician, and the Greek populations incorporate elements of one another, especially in burial practices for particular social groups. These patterns of mixed assemblages and practices serve to delineate between families or social sub-groups within an ethnic group, rather than act as ethnic signifiers. Shepherd’s findings thus remind archaeologists and historians that material culture does not necessarily reflect one’s ethnicity, but instead may serve specific purposes in different contexts; even more, these findings could indicate a plurality of identities in which ethnic boundaries shift. (IM, 2021)

Smith, Stuart Tyson. Wretched Kush: Ethnic Identities and Boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire. Routledge, 2003.

Much emphasis is placed on Egypt’s interactions with the Greco-Roman world, but understanding the relationship between Egyptians and ethnic others during the pharaonic era provides valuable perspective. Of critical importance to any meaningful study of race in antiquity are the various kingdoms of Nubia, which often rivaled or even surpassed Egypt in power and importance. Through examining the archaeological record at the colonial Egyptian settlement of Askut and cemetery at Tombos, Smith is able to demonstrate the ways in which shifting power dynamics between Egypt and Nubia radically altered the way ethnicity was performed and conceived. In Egyptian-occupied Nubia at the fortress of Askut, for example, Nubian cookware increased steadily over time. Residue analysis indicates that the food prepared in Nubian cookware differed from that prepared in Egyptian cookware, which suggests that—as in the American Southwest—colonial men likely formed households with indigenous women. These women deeply influenced the foodways of their Egyptian partners and the foodways and other cultural practices of their Egypto-Nubian descendants. Smith uncovered unambiguous evidence for such intermarriages (or at least entanglements) at Tombos, where women buried according to Kerman traditions shared space in tombs with men and women buried according to Egyptian traditions. (EM, 2021)

Yasur-Landau, Assaf. "Old Wine in New Vessels: Intercultural Contact, Innovation and Aegean, Canaanite and Philistine Foodways." Tel Aviv 32 (2): 168–191, 2005.

Yasur-Landau’s article analyzes the transmission of pottery styles between ethnic groups. He notes that the willingness of a group to adopt a foreign style of pottery is often dictated by its perceived usefulness and its compatibility with established cultural practice. One major factor that affected trade in pottery between groups was cultural differences in feasting. Paintings of Mycenaean feasts, for example, depict elites drinking with their peers from long-stemmed goblets, whereas depictions of Canaanite feasts showcase hierarchy. Typically, a seated ruling figure holds a large drinking bowl, while subordinate figures grasp increasingly smaller bowls. These inherent differences explain some of the material remains. Stemmed vessels like kylixes were imported to the Levant less often than other Aegean vessels. The pottery forms that enjoyed widespread popularity, on the other hand, were compatible with preexisting Canaanite vessels. The “chariot krater” is an example of such an Aegean borrowing, though such vessels appear to have catered to Levantine tastes. Yasur-Landau notes that they were “marketed almost exclusively outside the boundaries of Mycenaean culture.” The form and shape conformed to Levantine counterparts, while the ownership of chariots signified elite status in both cultures. These kraters had the virtue of introducing a novel visual element to feasts while allowing established local traditions to continue. Aegean-style cooking pots, like kylixes, Yasur-Landau argues, did not appeal to Canaanites because they altered accepted practice. When Aegean settlers moved to the southern Levant in the twelfth century, they imported their practice of cooking with a flat based jug placed adjacent to a hearth. Because contemporary Canaanite houses generally lacked hearths, this style of cooking does not seem to have crossed ethnic boundaries, except perhaps through intermarriage. (GK, 2023)

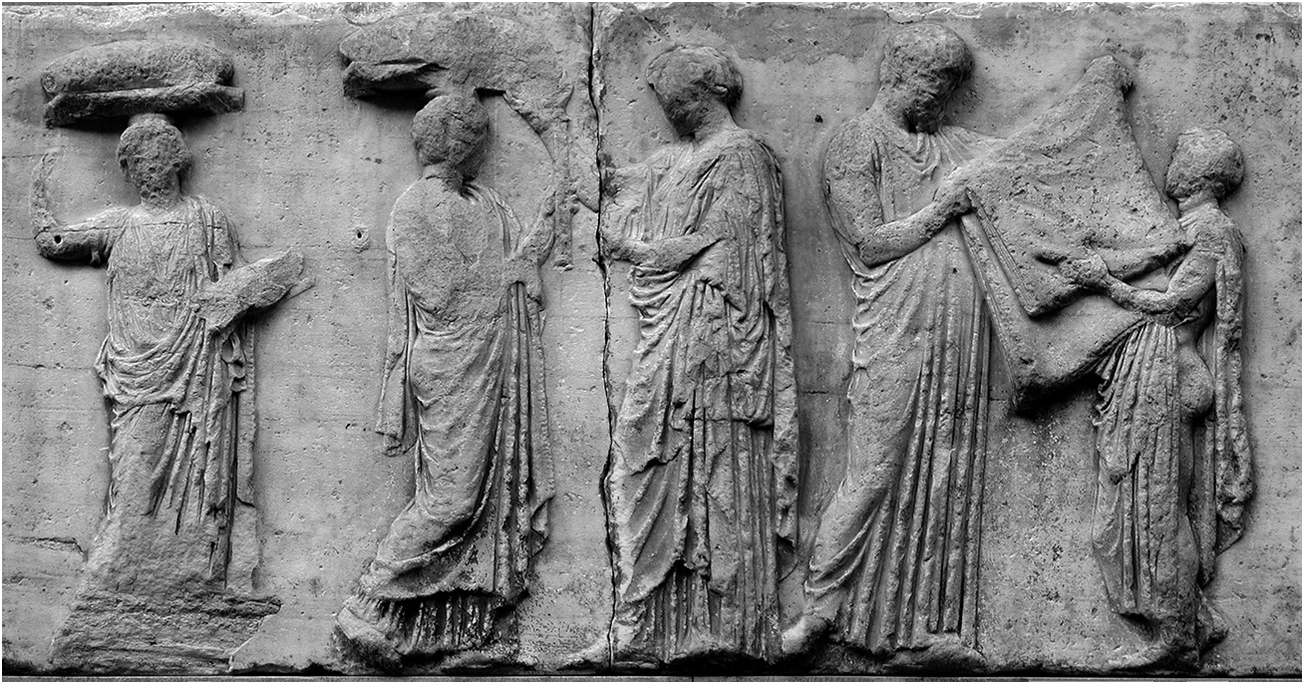

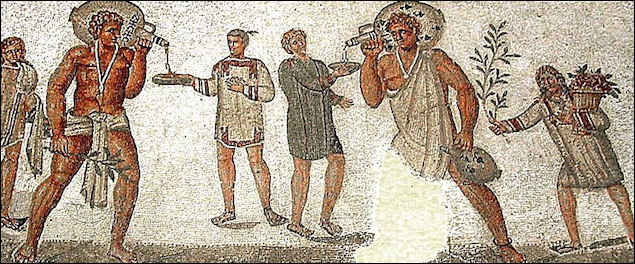

Race via ART & ART HISTORY

Perhaps the most recognizable axis for the utterance, reception, and codification of race is the artistic, which evades the entanglement of terminologies and explication required by the textual all the while assigning certain ideals of color, form, and being to its subjects. The following list of sources address a variety of corpora, both artistic and art historical, in examining the development of race in the portraiture and visual imagination of the Greco-Roman world.

Batchelor, David. Chromophobia. Reaktion Books, 2000.

A pioneering work in chromatic, or color, theory, David Batchelor’s Chromophobia is an essential piece of critical art theory which explores the constructions and manifestations of a cultural fear of color. Though Batchelor does not exclusively focus on the Greco-Roman world, he certainly sees the antiquity as the antecedent for dominant strains of thought concerning beauty, aesthetics, and the production of material purity. Chromophobia helps not only to answer the question, “why were Greek statues whitewashed?” but beyond this, “why does it matter that those Greek statues were original colored?”. This latter question is necessary when approaching the wide array of material remnants of antiquity, and further in understanding the apparatuses which construct and curate chromophobia.

Clarke, John R. “‘Just Like Us’ Cultural Constructions of Sexuality and Race in Roman Art,” in Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art History, ed. Kymberly Pinder, 2002.

As facile a claim that “the Romans are not like us” is nowadays, the centuries long effort to make coherent the face of the modern west alongside that of the Greek and Roman society is deserving of legitimate exploration. Clarke’s work interrogates rather than dismisses this masculinized and white face painted upon the Roman body, looking both at the artistic works of the era alongside their various receptions and inspired productions, namely between Renaissance humanists, and later European fascist movements, and their engagement with the ideologies and art of Roman empire. The piece is helpful in drawing out the art historical processes that falsify, legitimize, and whitewash the imagination of empire and is especially useful when considering the pressing dynamic of race and gender in the wider construction of supremacist movements. (ALR, 2022)

Donkor, Kimathi. “Africana Andromeda: Contemporary Painting and the Classical Black Figure,” in Classicisms in the Black Atlantic, eds. I. Moyer, A. Lecznar, and H. Morse. Oxford University Press, 163–194, 2020.

An artist whose primary medium is painting, Kimanthi Donkor examines representations of Andromeda – an Ethiopian princess, who was sentenced to be sacrificed to a sea monster as punishment for her mother’s hubristic vanity. Andromeda is eventually rescued by the hero Perseus. Donkor writes in an interesting and accessible fashion of his attempts while at the Tate Modern to discern Andromeda’s placement in the canon of Classical and classically influenced artwork. Specifically, he is concerned with the racial politics of her portrayal as Black or White. The piece is a wonderful exploration of a non-textual archive through the eyes of an artist. (ALR, 2020)

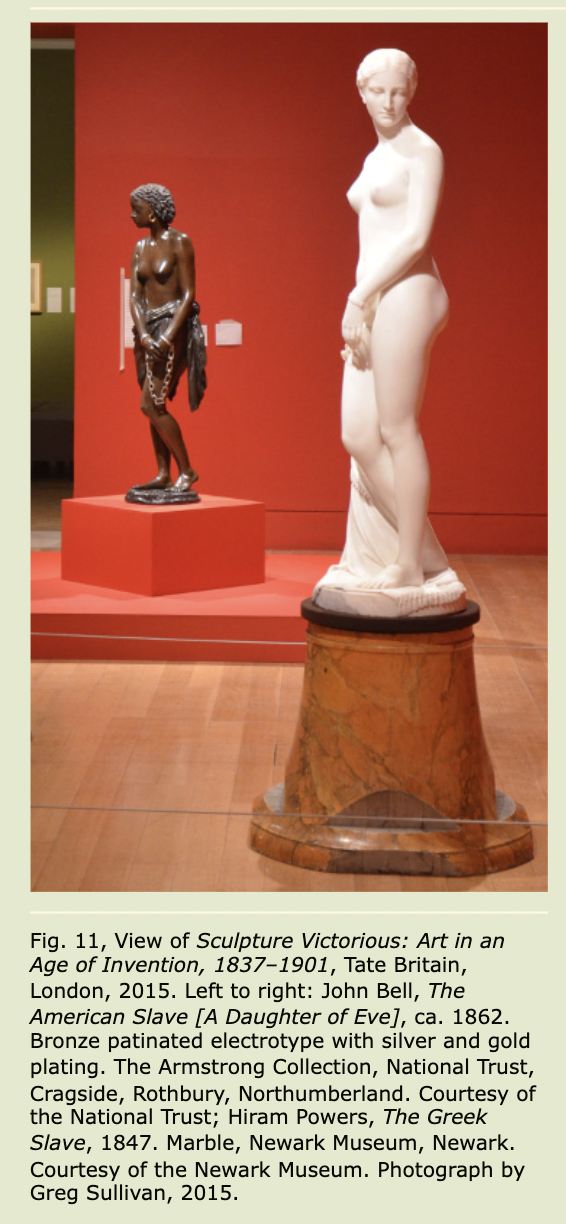

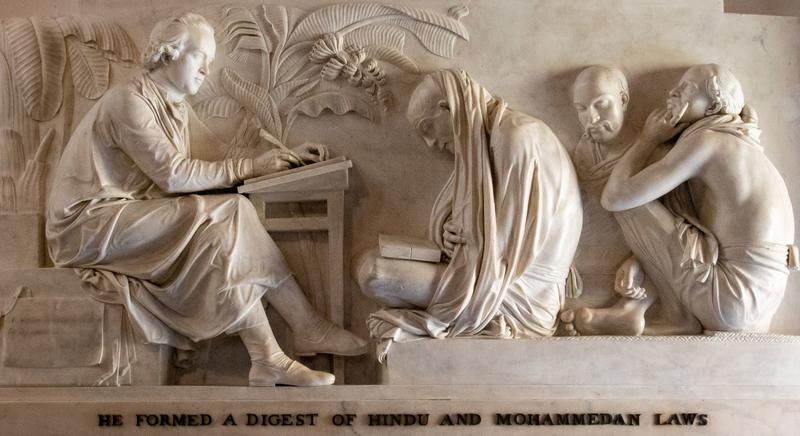

Droth, Martina and Michael Hatt, “The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers: A Transatlantic Object." Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide: A Journal of Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture

In this examination of Hiram Powers’ The Greek Slave, Martina Droth and Michael Hatt regard this famous classicizing 19th-century sculpture and its six commissioned marble copies as a multi-object, which drew new meanings from its various contexts (being displayed in slave markets in New Orleans, in the house of an abolitionist, and in juxtaposition with other statues in themed exhibits for various purposes). As an embodiment of whiteness, Christianity, and the imagined cultural link between the West and ancient Greece, The Greek Slave was one of the most widely reproduced sculptures of the 19th-century. When the artwork is considered in the context of the American enslavement of African peoples and simultaneously viewed as an embodiment of a still resonant racial politics that values an Anglo-Saxon ideal, the fame and controversy surrounding these statues is easily appreciated. The sculptures remain on display in different countries for different audiences and continue to be exhibited in new ways that create and continue the many conversations surrounding the piece. The visible differences between subject of the statue and the real women stolen, sold, and enslaved during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade when it was produced continue to drive discourse and have produced several reflective works in riposte (see left). (TNK, 2023)

Gates-Foster, Jennifer. “Achaemenids, Royal Power, and Persian Ethnicity,” in A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean, ed. J. McInerney. John Wiley & Sons Publishers, 175-193, 2014.

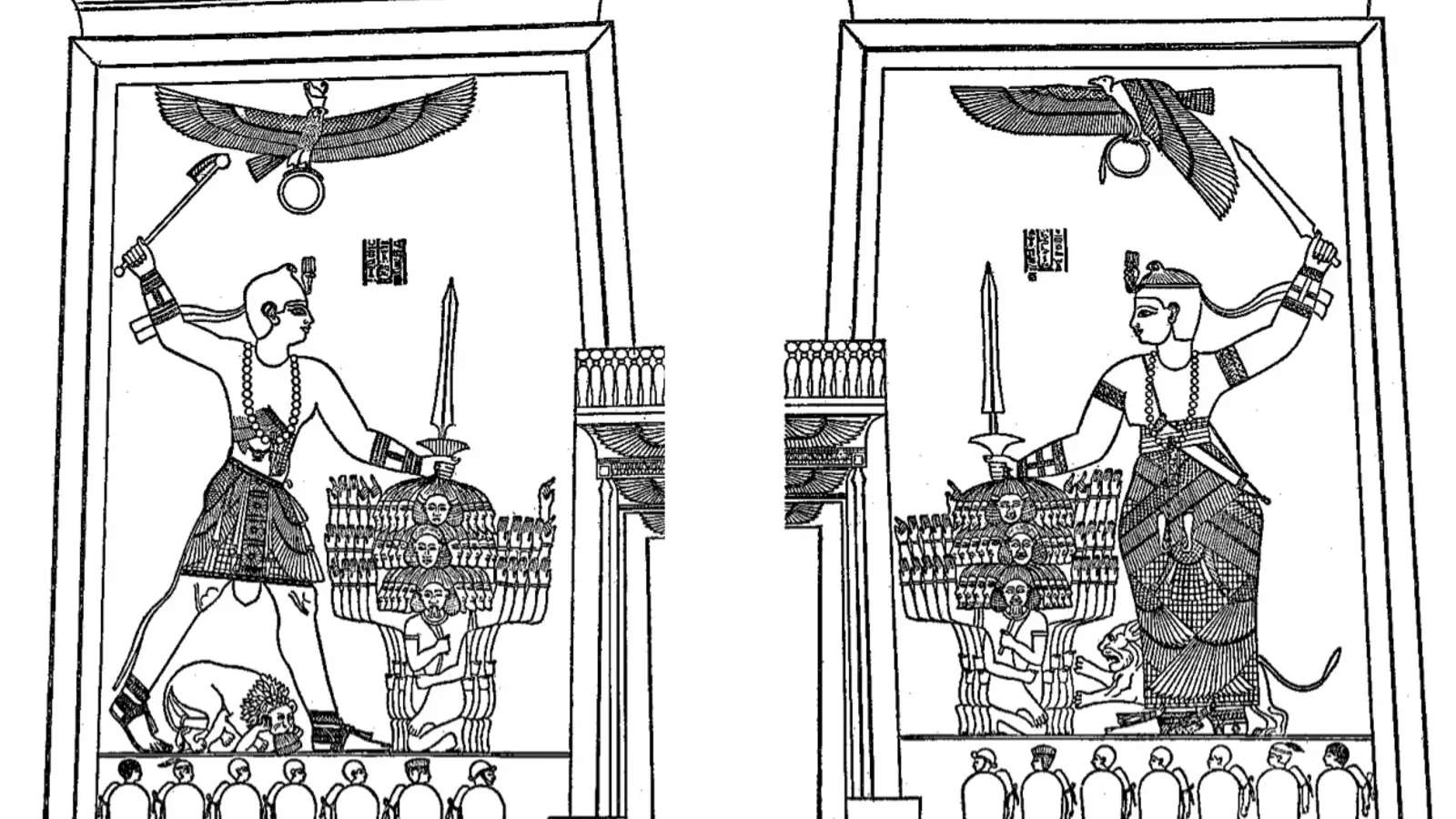

Jennifer Gates-Foster explores the interactions between ethnic identities and imperial government in the case of the Achaemenid Empire. She looks to the art of the Achaemenid empire and its incorporation of artistic customs and depictions of conquered peoples. The portrayals of different ethnic groups under Achaemenid control were central to the empire’s ideology, as they created a visual representation of the diversity and expanse of the state. Similarly, she indicates that Achaemenid kings gradually incorporated more art forms and iconographic motifs derived from the art of conquered groups to again emphasize the power of the king and the empire. Gates-Foster points out, however, that the interactions between the empire and ethnic groups in the satrapies was much more complicated, and the relationship between the two as displayed in art remains unclear. Gates-Foster’s approach to this work thus provides a useful lens for viewing state perceptions of ethnicity, not local perceptions. (IM, 2021)

Ferris, Iain. "The Enemy Without, The Enemy Within: More Thoughts on Images of Barbarians in Greek and Roman Art," Theoretical Roman Archaeological Journal, 22–28, 1996.

Ferris – continuing his previous analysis of the ‘barbarian’ character in ancient art – contrasts the Ludovisi Gaul by Epigonus (a Greek sculpture that had to be recreated in Rome) and a gilt diptych of the semi-barbarian general Stilicho at the Monza Cathedral Treasury. He does so in order to determine how these works provide insight into the social and cultural mindset of the creators and audience of their times. Where the Ludovisi Gauls sculpture depicts a nude man of great force and motion – “his body [as] wild power personified” – the sculpture of the Romano-Vandal Stilicho, possibly self-commissioned, has a static figure and stoic face. Additionally, the woman displayed in the Ludovisi Gauls is described as limp and lifeless (forever infertile), whereas Stilicho is portrayed with both his wife Serena and his son. Working within the framework of colonial discourse, Ferris finds that to some degree works of art like these serve to exoticize and create a sense of nostalgia for the strength and pure primitivism of the ‘barbarian,’ but also this stereotype is in direct opposition to the ideal character of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Ferris’ work is an excellent example of how approaches through art history can shed let on how author or artist perspectives shape these stock characters of the ancient world. (HC, 2021)

Franklin, John C. “Ethnicity and Musical Identity in the Lyric Landscape of Early Cyprus.” Greek and Roman Musical Studies 2 (1): 146-176, 2014.

Locals and immigrants resident on Cyprus inhabited a cultural crossroads in which Near Eastern and Aegean ideas had long met and mingled. This article discusses the influence of both Greek and Phoenician culture on the ethnic identity of Cypriots as shown through the artistic representation of lyres in the Early Iron Age. Franklin describes several artifacts that are taken to indicate foreign influence, including images from a Kouklian kálathos-vessel featuring a warrior playing a “Greek-style” round-based lyre in a manner perhaps reminiscent of Homer’s portrayal of Achilles. There are also several Cypriot bowls portraying scenes of music with different combinations of dancers, musicians, offering-bearers, and altars. In the scenes, the “orchestra” aligns with Levantine traditions in its combination of lyres, hand percussion, and double pipes. The presence of multiple lyrists in a musical group is reminiscent of the massed kinnor-lyres that performed in Jerusalem and of cultic lyre players from Cypriot Paphos known as kinyrádai. Though there is a distinction between eastern and western lyres in the Mediterranean—western ones having a rounder, more symmetrical structure, and eastern ones being more asymmetrical and thinner—depictions on Cyprus tend to be intermediary between the two. Franklin suggests that rather than viewing Cyprus as a “passive matrix for the implementation of foreign lyric identities,” it is likely that Cypro-Aegean hybrids had existed on the island since the Late Bronze Age, as implied by certain votive figurines. If so, the Iron Age lyres would be neither “Aegean” nor “Near Eastern,” they would be Cypriot (MB, 2024)

Hemingway, Seán, curator. “Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Showing July 5, 2022, to March 26, 2023.

While reading about and engaging virtually with polychrome is a key point of reorienting against the whitewashing of Greco-Roman art, the opportunity to witness this in person is all the more rewarding, an opportunity which is available to individuals in New York City until the Spring of 2023. Set at one of the largest homes to those very emblematic white marbles, the MET’s new exhibit which colorizes some of the same works sitting in their revised form just halls away is an important moment for curation at American art museums. Including an augmented reality component which lets visitors toggle between and imagine their own colorized worlds for the marbles, the exhibit opens the doors to not just study polychrome but to perhaps restore and repair the tradition. (ALR, 2022)

Huntsman, Theresa. “Hellenistic Etruscan Cremation Urns from Chiusi.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 49 (1): 141–50, 2014.

Ethnic signifiers are often particularly accentuated when associated with rites of passage. Thus, the objects utilized in such ritual contexts can offer exceptional insight into a culture. Terracotta funerary urns from the city of Chiusi in Etruria, may serve as a case in point. Manufactured as a sort of tomb for the Etruscan deceased, these objects provide a window into the funerary practices and rituals of the Etruscans. Chiusine urns required extensive labor by artisans, who carved militaristic scenes in the base as well as figures of the deceased on the lids and etchings of their names in Etruscan script. It seems, however, that the urn production was somewhat standardized. Each lid figure is of similar basic form, with only hair and facial features varying significantly between each one. Thus, thanks to this relatively systematic approach to their production, Chiusine urns offered an economically varied segment of society with “formal” burials. Because female figures on the lids recline just as males do in—a pose representative of banqueting—Huntsman further suggests that women were customarily included in banquets and also that the funerary ritual was comprised of a communal feast. In their distinctive celebration of the deceased, these urns demonstrate the prosperity of Chiusi, its relatively egalitarian ethos during the Hellenistic period, and its pride in its distinctive traditions. (AR, 2024)

Malamud, Margaret and Malamud, Martha. “The Petrification of Cleopatra in Nineteenth Century Art,” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 28 (1): 31–51, 2020.

Classicists Margaret Malamud and Martha Malamud present a fascinating case study of two nineteenth century renditions of Cleopatra: one by William Wetmore Story, a white sculptor, and another by Edmonia Lewis, a Native American and African American sculptor. Story made the deliberate choice to give “African features” to his Cleopatra (1860), a drastic deviation “from classicizing portrayals of the queen” (it is important to note that this was received as an artistic choice and not as a statement of racial identity). On the other hand, Lewis chose to portray Cleopatra as white in The Death of Cleopatra (1876). This poignant article examines Lewis’s choice, which was perhaps established by her “encounters with white male artistic and literary fantasies of Cleopatra and her legendary sexual allure…” along with her “awareness of contemporary racist associations with excessive Black female sexuality.” With explorations of the ways racism functions even within Black representation, this is a relevant read for those who wish to learn more about the talented artist Edmonia Lewis and about race through artistic reception. (RT, 2021)

Martin, S. Rebecca. “Ethnicity and Greek Art History in Theory and Practice,” in Theoretical Approaches to the Archaeology of Ancient Greece: Manipulating Material Culture, ed. Lisa C. Nevett, University of Michigan Press, 143–63, 2017.

Alongside an analysis of Greek artistic conventions for representing ethnicity, Rebecca Martin examines the relationship between representation and identity in Greek art history. Through her discussion of naturalism and illusionism, she complicates current scholarly understandings of ethnicity in Greek art and proposes that representations of difference in Greek material culture are neither consistent nor documentary. She illustrates her main points via an in-depth case study of Alexander’s Sarcophagus, a large (3 x 1.5 m.) and elaborately carved funerary monument found in the Ayaa Nekropolis near Sidon (see below). Martin problematizes modern interpretations of this fourth century BCE artwork as Greek or Hellenistic and favors, instead, a Phoenician and Sidonian reading. She writes about the role of patronage, asserting that “perceptions of ethnicity of artist and patron can color interpretation.” She also warns that the privileging of formal or compositional Greek elements in art can lead to a misclassification that disregards the artwork’s context, such as its patronage or site of manufacture. Finally, she emphasizes the value of ethnicity as a tool for “uncovering the humanity of ancient artwork,” proposing that archaeology must utilize a contextualized, sensitive exploration of material culture in the ancient world. (EGC, 2024)

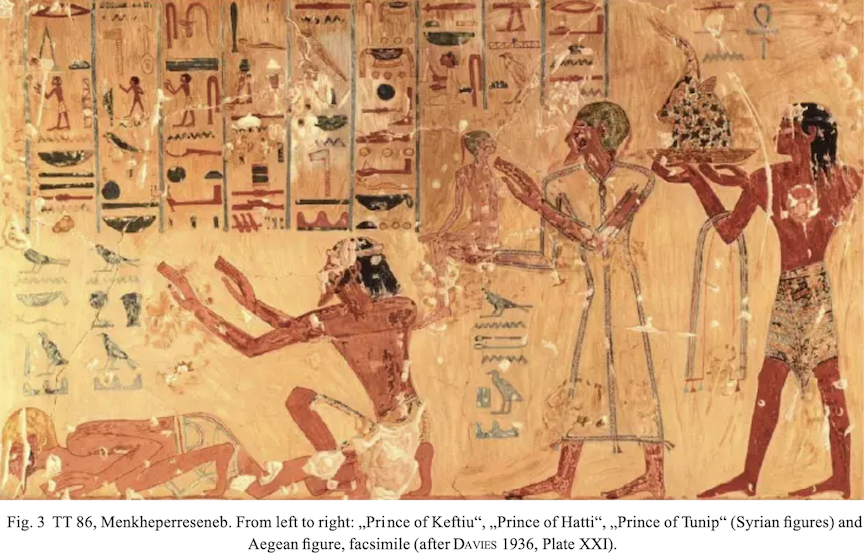

Matić, Uroš. “Minoans", kftjw and the "islands in the middle wɜḏ wr. " Beyond ethnicity.” Ägypten und Levante 24: 275–292, 2014.

This paper rejects the historical classification of the Minoans as an ethnic group. Such categories fail to provide a responsible reconstruction of the past and instead reflect a nineteenth-century obsession with racial, colonialist, and nationalist discourse. Uroš Matić argues that ancient identity categories are far too complex to organize into straightforward labels vis-à-vis the archaeological record. To illustrate this point, Matić critiques the easy equation of the Minoans with the Egyptian term kftjw. The historic justification for the conflation of the two terms comes from Theban Eighteenth Dynasty tombs in which Minoans—themselves picked out by physical characteristics such as hair and skin color—are labeled kfjtw. This interpretation gained broad acceptance even though from a grammatical perspective, kftjw refers to a geographic region rather than a people. Furthermore, the term kftjw was not exclusively used to label Aegean figures in the Theban tombs; it was also employed to reference Syrian and Syrian-Aegean hybrid figures. For instance, the Tomb of Menkheperreseneb depicts three Syrian-type figures in the first register, one of which is referred to as the “prince of kftjw .” In the past, these labels have been disregarded as mere inconsistencies or artistic mistakes in order to uphold the erroneous equation of Minoans with kfjtw. By contrast, Matić argues that these “inconsistencies” are meaningful in their own right, and indicate that the New Kingdom Egyptians understood a conceptual link between the Aegeans and Syrians. (EC 2023)

Morales, Helen, curator. “Harmonia Rosales: Entwined”. Art, Design, and Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara. Showing January 19, 2022, to May 1, 2022.

Bringing together the mythologies and conceits of Yoruba and Hellenic, and otherwise Western world, the work of Harmonia Rosales allows its viewers to imagine a Classicism which is Black in its presentation, figural representation, and aesthetic sensibility. The exhibit, which is curated around the very tension of its composite parts, hosts alongside the works of Rosales a series of talks which speak to the import of Black Classicism and its visual entrapments, including Classics professor Dan-el Padilla Peralta’s lecture “The Greeks are Then, the Orishas are Now” and religious studies professor Elizabeth Pérez’s “Decolonizing the Orishas: Harmonia Rosales & the Un-Whitewashing of Black Atlantic Divinity”. The collection is an important source of examination to look outside literary reception to consider instead the very face and human subject of Black Classics. (ALR, 2022)

Savoy, Bénédicte and Sarr, Felwine. “The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics,” trans. Drew Burk. Commissioned by Emmanuel Macron, 2018.

In 2018, following decades of political pressure and social movements, the popular tide in France had shifted towards considering the possible restitution of the artifacts France had pillaged, looted, and otherwise unethically acquired during its colonial reign of northwestern Africa. As such, PM Macron commissioned French art historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese scholar Felwine Sarr to write a report on the impact of the lost artifacts on the African continent and the possible futures restitution may bring about. The report is a triumph of public intellectualism, bringing together centuries of context to the matter of cultural theft. The report humanizes “the artifact” not as an evidentiary thing that provides truth within the academy but as a holder of immense cultural and personal value, one whose absence deprives people of a past and whose presence is necessary in building futures. While archaeologists working with antiquity continue to excavate lands in whose presence they have little stake, an undeniably important pursuit, the Savoy-Sarr report is a grounding work that reframes the narrative life of artifacts and suggests the value of their remaining in their countries of origin. As of February 2021, no artifacts have been restituted to Africa from France. (ALR, 2021)

Skovmøller, Amalie. Facing the Colours of Roman Portraiture: Exploring the Materiality of Ancient Polychrome Forms. De Gruyter Press, 2020.

While several curatorial projects and articles have dedicated themselves towards the work of understanding polychrome in antiquity, Skovmøller’s is the sole monograph which attends to these issues and their various implications in their totality. Of great interest to Skovmøller are the processes portraiture coloring and the economies which produced the dyes and textiles used in this work. In addition, Skovmøller carefully works through the meaning of coloration thinking about the work of polychrome not only Roman portraiture’s reception but to the publics which would have viewed these works. While the work of ethnicity is tangential and not necessarily focalized in Skovmøller’s work, it is undeniable that polychrome, and its erasure, have shaped our understanding of race in antiquity. Further, and critically, in her examination of the systems of production for the various paints and dyes used in Roman portraiture, the global economies and artistic practices necessary for the development of “the Roman man” come into focus. (ALR, 2022)

Tanner, Jeremy. "Race in Classical Art." Apollo 173 (584): 24-29, 2011.

Interpretations of the past are often colored by the biases of the present, and this is certainly true when it comes to ancient art. In his article, Jeremy Tanner briefly summarizes many of the issues in historic interpretations of depictions of Black individuals in Greco-Roman art and advocates for a methodological shift in analyzing these images. Tanner discusses how many historic analyses of Black figures in ancient art were used to reinforce racist ideas and the subordinate position of Black people in the racial hierarchy. This connection between ancient Africans and contemporary Black people was also used to connect the ancient Greeks with contemporary White people of European heritage. Tanner pushes back on this connection and argues that these analyses likely do not correspond to how Greco-Roman peoples thought of themselves racially. By focusing on exaggerated traits as indices of racial difference, as well as the specific form and context of a depiction, Tanner argues that it is possible to gain insight into how racial ideas underlay ancient iconography. Tanner also emphasizes the need to take concepts of class and social status into account in these analyses. By providing a framework for a richer and more nuanced analysis of ancient art, we can better understand the form and impact of ancient concepts of race and racism as well as their artistic legacies in more modern times. (JB, 2024)

Race via CRITICAL RACE THEORY

A school of thought pioneered by Black scholars in the mid 1980s, Critical Race Theory (CRT) transformed the reading of literature, history, law, and nearly every other facet of the academy by suggesting that race, especially white supremacy, permeates the fiber of the world. CRT is a framework that can be widely applied and serves to question the fundamental assumptions of the scholarship and knowledge production through the complication of racial(ized) thought. Of the following sources Omi and Winant serve as an introduction to the topic, while other sources provide examples of how CRT can be utilized in classical research or suggest innovations to the framework itself.

Derbew, Sarah. Untangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Not since Frank Snowden’s work on Blackness in antiquity in the 70s and 80s, which predates the vast growth of CRT in academia, has a monograph so wholly and comprehensively taken on the titular issue. Derbew’s book, which grounds itself between critical race theory and performance studies, is nearly encyclopedic on the matter, bringing into its frame material, literary, historiographic, and geographic/ethnographic material concerning the figural Black person in ancient Greece. The huge archive Derbew constructs in the appendices of this work are enough to serve as an indispensable resource for any student of race in antiquity. Yet more so, it is her erudite analysis of this material which itself cleaves towards answering the question, “what did black skin mean in antiquity?”, crafted through the examination of several landmark works of contemporary theory that makes the work such a important piece at the intersection of CRT and Classics. (ALR, 2022)

Haley, Shelly. “Be Not Afraid of the Dark: Critical Race Theory and Classical Studies,” in Prejudice and Christian Beginnings: Investigating Race, Gender and Ethnicity in Early Christian Studies, eds. Laura Nasrallah and Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, Fortress Press, 2009.

Haley, a Black woman and scholar of Latin poetry, masterfully explores how the two often isolated fields of Classics and Critical Race Studies can be meaningfully and revealingly placed into dialogue. Moving through some of the best known Latin works – among them selections from Catullus and Vergil – Haley puts her own translations alongside well known alternatives in order to demonstrate the power of taking a common Latin adjective instead as a racial descriptor. This work is especially useful to readers of Latin, for whom the text demonstrates how race and racial thought are encoded in poems that are often taken as race-neutral. (ALR, 2020)

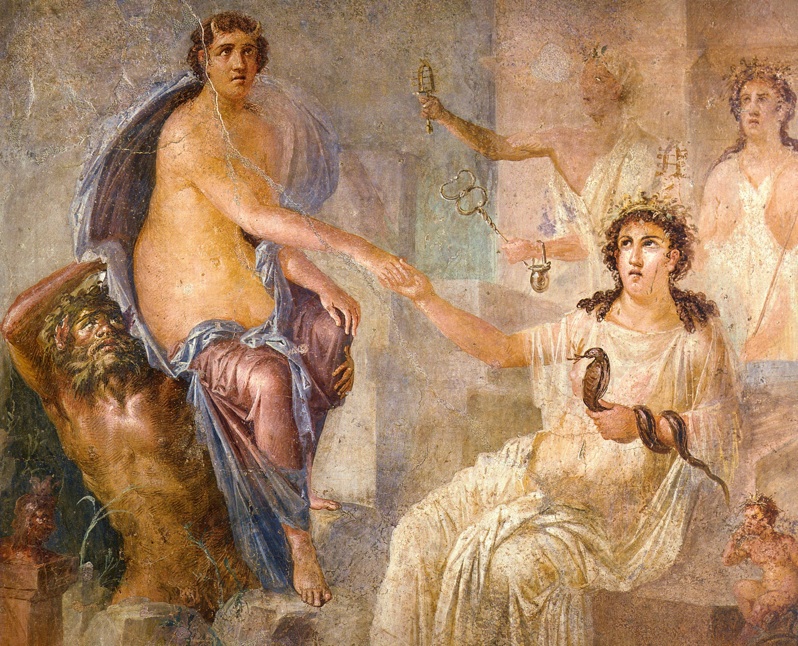

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts”. Small Axe 12 (2): 1–14, 2008.

In her studies of “the afterlife of slavery,” Saidiya Hartman has forged new ground in interpreting Atlantic slave trade documents and in archival studies more generally. “Venus in Two Acts” is Hartman’s attempt to solve the mystery of Venus’ abundance and meaning for enslaved women in the Caribbean. Reading the diaries of Thomas Thistlewood – a cruel and perverse slavemaster who primarily wrote in Latin – Hartman demonstrates the violence of archives that serve to silence Black slaves. Aside from its overt connections to antiquity, “Venus in Two Acts” is essential reading for the student of CRT for its discussion of critical fabulation. In Hartman’s own words, “The intention [of critical fabulation] isn’t anything as miraculous as recovering the lives of the enslaved or redeeming the dead, but rather laboring to paint as full a picture of the lives of the captives as possible. This double gesture can be described as straining against the limits of the archive to write a cultural history of the captive, and, at the same time, enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration.” This tool, widely and keenly applicable to the Classical canon, which is often marked more by its silence than its voice, will enhance the theoretical approach taken by any scholar. (ALR, 2020)

Hendricks, Margo. “Coloring the Past, Rewriting Our Future: RaceB4Race.” Speech at Race and Periodization conference at the Folger Institute, 2019.

Speaking at a panel on Race and Periodization, literary theorist Margo Hendricks called for the abandonment of Premodern Race Studies – something she sees regularly and unproductively performed in academic settings – in favor of Premodern Critical Race Studies. The impact of the word “critical” here adds an important valence, one that pushes against the white academic seizure of Premodern Race Studies. Premodern Critical Race Studies, Hendricks notes, “actively pursues not only the study of race in the premodern, not only the way in which periods helped to define, demarcate, tear apart, and bring together the study of race in the premodern era, but the way that outcome, the way those studies can affect a transformation of the academy and its relationship to our world. [Premodern Critical Race Studies] is about being a public humanist. It’s about being an activist.” Clearly, the field of Critical Race and antiquity is still actively forming. Listening to the scholars who are currently pushing the boundaries of conceptualizing race in antiquity and reshaping these limits is vital. (ALR, 2020)

Isaac, Benjamin. The Invention of Race in Classical Antiquity. Princeton University Press, 2006.

Isaac never marks out his method as being in line with CRT – partly because his primary interest is in the development of antisemitism as a product of antiquity rather than anti-Blackness – but the text is placed here as it makes not just a claim of race, but of racism, which is explored through the lens of white supremacist values. In many ways, Isaac is the antithesis to Snowden in Before Color Prejudice (mentioned earlier in the bibliography), as he finds there to be a direct line of development between Greco-Roman supremacy and European white supremacy, which he substantiates in the reading of imperial texts. Isaac is one of the few scholars of Classics who suggests that racism is itself ancient, and this is a hypothesis, contested though it may be, that is worth unpacking and sitting with. The text will be particularly useful for students of Jewish history and those interested in the formation of genocidal thought and holocaust, but serves a broader function of forcing confrontation with racism itself. (ALR, 2021)

McCoskey, Denise Eileen. “Race before ‘Whiteness’: Studying Identity in Ptolemaic Egypt.” Critical Sociology28 (1–2): 13–39, 2002.

Denise McCoskey introduces the lens of racial theory to understand how ethnic identity was constructed in Ptolemaic Egypt and to illustrate how the study of race can reframe our conceptions of the ancient world. Traditionally, scholars of Ptolemaic Egypt have focused on the mutability of ethnic categories, especially with reference to military men and governmental officeholders under the Macedonian government. Yet, as McCoskey points out, the use of “ethnicity” as a framing device is too limited to account for the extreme power disparities evident in Ptolemaic Egypt. The subordination of the vast majority of native Egyptians to a privileged category of Greek immigrants forces a recognition that a racialized hierarchy had been created. McCoskey explores evidence of highly racialized rhetoric in literature and documentary texts, and she notes that almost without exception high office and tax breaks were reserved for individuals who bore Greek names and either were Greek or else performed a Greek identity in the course of their duties. Significantly, McCoskey’s preference for utilizing the term “race” rather than “ethnicity” is not because it claims phenotypic difference as paramount but rather because “it connotes, and refers investigation to, issues of power.” (CG, 2024)

McCoskey, Denise. Race: Antiquity and its Legacy (Ancients and Moderns). Oxford University Press, 2012.

In Race: Antiquity and its Legacy, McCoskey provides the most salient generalist’s overview to race and ethnicity in the ancient world. McCoskey’s thesis is that race in antiquity is distinct from the way race comes to function after the colonial era but that ancient ideas concerning race gave way and perhaps even gave power to more modern conceptions. While this notion might seem obvious, McCoskey’s text eruditely guides the reader through these ideas with accessible analogies. For example, she places the dichotomy of “Black versus white” in dialogue with the sense of “Greek versus Barbarian” in the post Persian War context. Race: Antiquity and its Legacy, while certainly not an anthology, provides numerous primary sources in a distilled and contextualized form, thereby granting its reader not only theory but also applicable further reading. This work is a necessary companion to any formal introduction of race and ethnicity in the ancient world. (ALR, 2020)

Omi, Michael and Winant, Howard. Racial Formation in the United States. Routledge Press, 1994.

Understanding race and ethnicity in the ancient world does not necessarily require experts on antiquity to give meaning, context, and important intervention to the texts and materials considered. Michael Omi and Howard Winant are sociologists concerned with America in the modern era, yet their construction of racial formation theory is a valuable model for thinking through ancient contexts. Most importantly, Omi and Winant challenge common notions of race as fixed and codified, proposing instead an idea of race as unstable, dynamic, and adaptive to its milieu – especially in the context of political and social conflicts. This theory is laid out primarily in chapter 4, “The Theory of Racial Formation,” which helpfully defines and complicates the terms race, racialization, and racialized. Racial Formation in the United States stands out in the bibliography of any student of Classics or ancient studies, as it gives an insightful and timely “outsiders” take on the matters at hand. (ALR, 2020)

Rankine, Patrice. “Classics for All?: Liberal Education and the Matter of Black Lives,” in Classicisms in the Black Atlantic, eds. I. Moyer, A. Lecznar, and H. Morse. Oxford University Press, 267–289, 2020.

Rankine’s examination of issues of access and delimitation of thought in the post-Obama era lends itself to an important discussion of the point of Classics itself. Rankine notes that Classics for All, a campaign to give universal access to Greek and Latin language learning for school children, is problematized by “[its] idea of unidirectional mastery, namely that the recipients benefit from the discipline and leave it as pristine as they found it.” Rankine draws a meaningful analogy between the loss of particularity in approaching Classics and the Neoliberal flattening of the Black Lives Matter movement. (ALR, 2020)

Samuels, Tristan. "Herodotus and the Black Body: A Critical Race Theory Analysis," Journal of Black Studies 46 (7): 723–741, 2015.

In this article, Tristan Samuels confirms the existence of Blackness in ancient Egypt and reorients our understanding of the origins of anti-Blackness in Western thought. In examining the writings of Herodotus, Western scholars of the late 20th century actively engaged in the “denial of ancient Egypt’s Blackness” by acknowledging the “so-called Black features” of Egyptians (like hair texture or skin tone) described in ancient Greek writing, while also maintaining that the “ancient Egyptians could have been anything—but Black.” This erasure is the product of a white supremacist lens in Greco-Roman studies that “equates ‘Negro’ with inferiority and ugliness” but according to Samuels, this lens started before 20th century academia and even before the transatlantic slave-trade. Drawing on Herodotus 3.101, he argues that the Greek historian ‘othered’ the Black body, promoting ideas of the hypersexuality, savagery, and cowardice. Here, Samuels illustrates both the prevalence of Blackness in the Classical sphere and argues for the “antiquity of anti-Black racial prejudice” in Western thought. (HH, 2021)

Umachandran, Mathura. “Disciplinecraft: Towards an Anti-racist Classics”, TAPA 152 (1): 25–31, 2022.

Opening with the trenchant question, “what would it take to imagine and to materialize an anti-racist discipline of Classics”, Mathura Umachandran’s enormously quotable essay found in an equally important issue of TAPA swirling around the epistemic import of “Classics after COVID”, is indispensable to a critical examination of the field of Classics. Balanced on a series of suggestions and attended by a wealth of citations, from Agbamu to Wynter, to guide any rigorous effort to render anti-racist the mechanics of the field, this piece, despite its relative brevity, coheres a wide variety of anti-racist efforts implored by, and suggestibly against, the larger political movements of academia. It is a valuable resource which merits frequent return and handles its examined subject with a necessarily critical insider’s eye. (ALR, 2022)

Race via CITIZENSHIP, IMMIGRATION, TRADE ENCLAVES, & INTERMARRIAGE

The communities of antiquity, especially those in well-established city-states, were not comprised only of citizens and slaves, but of various people who might otherwise be called “immigrants” — expats, refugees, children of the foreign born. These identities were often deeply political and the court cases, laws, and treaties related to them formed the legal core of many cities. The following list of sources considers the hierarchies and dynamics between citizen and foreigner, especially viewing classes of individuals who fall outside this binary, including metics, and the ways individuals could move between these sects, including intermarriage.

Aneziri, Sophia. “World Travellers: The Associations of Artists of Dionysus,” in Wandering Poets in Ancient Greek Culture: Travel, Locality, and Pan-Hellenism, eds. R. Hunter and I. Rutherford, Cambridge UP, 217–236, 2009.

Sophia Aneziri examines the Artists of Dionysus during the Hellenistic and imperial period and their formal associations. The development of festivals and contests dedicated to artistic performances created an environment which attracted participants and audience members from a variety of regions in the Hellenistic world. Interestingly, several of these associations—including two of the largest ones—defined themselves by the places they travelled to rather than their place of origin. As for individual members, their homelands were less relevant than their identity as a member of one of these associations. Membership also had concrete political and social meaning, allowing this membership to function as a form of citizenship for the individuals. In many ways the guilds functioned as their own states, although individual members did not necessarily have citizenship in the cities where these associations were situated. The political and social functions of these organizations included dispatching emissaries to festivals and competitions as well as engaging in diplomacy with “cities, kings, and later emperors.” As members of these ethnically heterogeneous associations, individual artists were granted privileges of security and inviolability that effectively granted them protections akin to or greater than those of the citizens of the city states they visited. (MB, 2024)

Andrade, N.J. "Drops of Greek in a Multilingual Sea: The Egyptian Network and Its Residential Presences in the Indian Ocean." Journal of Hellenic Studies 137: 42–66, 2017.

This article delves into the significant impact of the Hellenistic Greek world on the Indian Ocean, highlighting the interactions between Greek-speaking Egyptians and individuals in India known as Yavanas during the first and second centuries AD. It examines if these Roman Egyptian merchants established permanent communities in Indian ports and investigates the appropriation of the term 'Yavana'—originally referring to Greeks in northern India—by certain inhabitants near the Gulf of Barygaza and the western Ghats. The narrative is enriched by examining sources such as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, authored by a figure deeply involved in these multicultural exchanges. This document and others provide insights into how these expatriates shared their language and culture and played a significant role in the broader commercial and cultural network connecting regions across the Indian Ocean. This led to the creation of residential settlements by these communities which became hubs for sharing local knowledge. The piece touches on epigraphic evidence from Indian sites like the Hoq Cave on Socotra and Buddhist monasteries where there are inscriptions left by self-described Yavanas. These inscriptions, along with Tamil poems, suggest a blend of identities and cultural interactions facilitated by maritime activities. (DN, 2024)

Boegehold, Alan. “Perikles’ Citizenship Law of 451/0 BC.” in Athenian Identity and Civic Ideology, eds. A. Boegehold and A. Scafuro, Johns Hopkins University Press, 57–66, 1994.

Alan L. Boegehold explores the motivating factors behind an Athenian law which limited Athenian citizenship to “men born of two Athenians.” Boegehold notes that the Greek philosopher Aristotle explained this law as a way to reduce the already large body of citizens; he argues, however, that this does not explain the motivations for limiting the population of citizens. Boegehold tackles this issue by first exploring the perks of citizenship, such as protections against torture and arrest, the ability to hold office, and the right to own and inherit property. This last perk is the most important to Boegehold, given the limited amount of land in Attika, the region surrounding Athens. He argues that previous laws of citizenship were unclear, leading to many legal disputes and subdivisions of land. Thus, Perikles’ redefinition of citizenship was motivated by a desire to limit the population, as Aristotle said, so as to ameliorate these recurring problems. Boegehold’s chapter therefore offers an example of how economic and political factors influence the legal definitions of ethnicity (IM, 2021)

Čulík-Baird, Hannah, “Archias the Good Immigrant,” Rhetorica 38 (4): 382–410, 2020.

Much of the contemporary writing analyzing Cicero’s Pro Archia explores its role as a defense for the arts and humanities and neglects the underlying nature of the speech. In this article, Hannah Čulík-Baird focuses on contextualizing the larger political and cultural relations within the Roman Period during Cicero's lifetime that resulted in the case against the poet Archius and Cicero’s defense on his behalf. Much of Cicero’s language in this oration elides the defendant’s Syrian’s heritage in favor of his status as a Hellenized individual, capable of bringing benefits to the Roman Empire. Cicero is thus acknowledging anti-immigrant sentiments in Rome by framing Archias as a “good immigrant.” This rhetoric in Pro Archia gives scholars insight into the social and political debates concerning the immigration to Rome of individuals and groups from its conquered and surrounding nations. (TNK 2023)

Demetriou, Denise. Negotiating Identity in the Ancient Mediterranean: The Archaic and Classical Greek Multiethnic Emporia. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Drawing upon a wide range of historical, archaeological, and anthropological evidence, Denise Demetriou explores the multifaceted nature of identity formation within the cosmopolitan emporia of the ancient Mediterranean. By focalizing port cities and nodes in which different ethnic groups regularly came into contact, Demetriou emphasizes the importance of multicultural interaction to the formation of a shared “Mediterranean” identity among Phoenicians, Greeks, Etruscans, and others. For example, polytheism and fluidity in religious identity led over time to greater similarity and more communal ritual practice. Similarly, the fact that artisans from different cultural backgrounds often shared workshops in cosmopolitan settings resulted in increased visual hybridity and intercultural legibility. Overall, she suggests that civic identity was likely more salient than racial or ethnic identity in such commercial centers. Demetriou argues that authors who are invested in highlighting contrasts between “Greek” and “Barbarian” identities, or between the colonized and their colonizers, have largely ignored areas of common ground and understanding. Identity was not fixed, she states, but rather shaped by various factors such as social status, ethnicity, religion, and material interaction. (SC, 2024)

Dietler, Michael, and Carolina López-Ruiz. Colonial Encounters in Ancient Iberia: Phoenician, Greek, and Indigenous Relations. University of Chicago Press, 2009.